50 years ago, Salvador Allende became the President of Chile. A number of experts agree that this “Chilean choice” was the first peaceful political victory of the pronounced left-oriented forces in the Western Hemisphere. How are Chileans defending their democracy today?

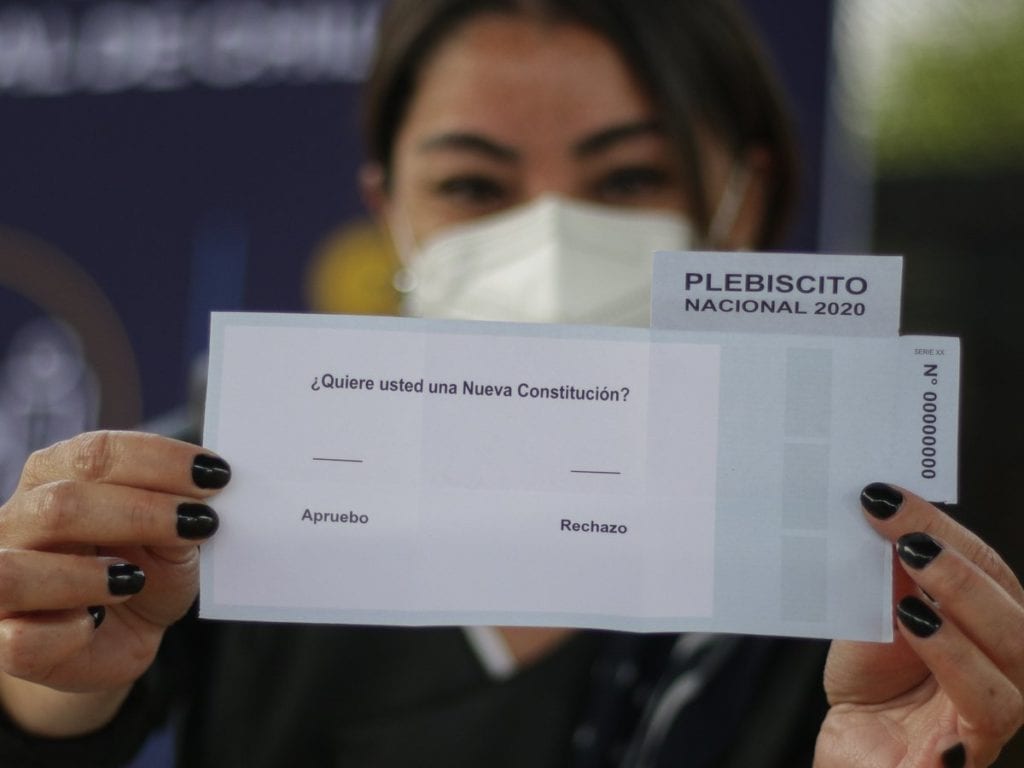

On October 25, a very important event took place in Chile, which marked a new milestone in the modern history of the country. On this day, the Chileans took part in the National Plebiscite, at which two questions were raised: “Do you want a new constitution?” – “Yes” was answered by 78.26% of Chileans.

Another question: “If yes, which body should develop it? A constitutional assembly made up of half of parliament members and half of elected citizens – or 100% of elected citizens?” – 78.99% of those who answered “yes” were in favor of the second option.

The main question of the National Plebiscite in Chile on October 25: “Do you want a new constitution?”

Following the results of the National Plebiscite, 155 representatives will be elected to write the new Constitution of Chile, roughly half men and women. In addition, there is a quota for indigenous peoples.

The Chilean leadership made the decision to revise the main constituent document of the state against the backdrop of protests in October 2019. Last year, the municipal government of Santiago once again raised the price of metro fares by 30 Chilean pesos. At the very beginning scattered groups of the student movement protested against, as it seemed at first glance, such a slight increase in value, but gradually tens of thousands of people began to join them, including in other large cities.

The rise in the price of the metro pass in the Chilean capital was a catalyst for social discontent and tension. The protesters began to demand broad economic and democratic reforms in the country, as well as the resignation of the president, the dissolution of the government and parliament. The disaffected smashed metro stations and robbed shops.

After the escalation of this conflict, the Chilean leader Sebastian Piñera (Spanish – Miguel Juan Sebastián Piñera Echenique) agreed to cancel the rise in the cost of metro tickets, and also slightly increased the minimum wages and pensions, however, the protests continued and gradually began to gain traction. On October 18 last year, for the first time in 30 years of democracy in Chile, a state of emergency was declared, the military entered the capital in armored vehicles. Social unrest and protests in the country continued and stopped only in March 2020, when a general quarantine was introduced in Chile.

Social protests in Santiago de Chile, November 2019, Source: La Jornada.

In order to prevent protests from flaring up with renewed vigor after the partial lifting of quarantine restrictions, the Chilean government has proposed a constitutional reform. At first glance, this option suited everyone – the protesters received hope for a complete renewal of Chilean institutions, and Piñera, whose approval rating fell to -72%, was able to calmly remain in the presidency until the end of his term, which expires in 2022.

From the very beginning, the National Plebiscite was scheduled for April 11, but due to the outbreak of the coronavirus in the region and the complete lockdown in the country, the vote was postponed. The procedure, which ended in October, was attended by about 14.5 million residents. It is worth noting that this turnout is significantly higher than in the last presidential elections in 2017, when, according to the Chilean electoral service, about 6.7 million people took part in the voting. Thus, then the turnout was below 50%.

After the National Plebiscite, the Chileans will face a long process of updating the main constituent document of the state. The peculiarity of the procedure that has begun is that the leading subjects that will carry out large-scale preparation of the document will not be traditional parties: “right”, “left” or “centrist”. The writing of the Constitution will “fall on the shoulders” of the Constituent Assembly. According to the results of the October 25 vote, the majority of Chilean citizens decided that all 155 members of the body would be elected by voting. In this case, a mandatory requirement will be that the Constituent Assembly will equally include men and women in order to achieve parity.

Chileans celebrate the triumph of democracy following the announcement of the results of the National Plebiscite on October 26, 2020 in Santiago de Chile. Source: CNN en Español.

Such an event is certainly intended to close the long cycle of Chilean history. On September 11, 1980, Chile’s new Constitution was adopted. Then, according to official data, about 67% of voters supported the adoption of the main body of laws of the country. The 1980 document provided for the consolidation of the powers of the executive branch, the National Security Council was created as a decision-making body, and the priority participation of the armed forces in all areas of life was retained again. In addition, when the Parliament was formed, the proportional representation system was abolished, and a part of the Upper House was appointed.

8 years later (October 5, 1988), a National plebiscite was held. Through this procedure, Augusto Pinochet (Spanish – Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte) tried to extend his tenure in power for another eight years. According to the results of the vote, 55% of citizens then voted against the extension of Pinochet’s mandate, and 45% were in favor. This outcome of the plebiscite opened the way for the first free elections in many years.

In 1988, the Union of Parties for Democracy “Concentration” (Spanish – Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia – “Concertación”) was created, and the presidential elections were held on December 14, 1989. The victory in the electoral process was then won by the leader of the Christian Democrats Patricio Aylwin (Spanish – Patricio Aylwin Azócar), which marked the transition to a new system. Nevertheless, the “dismantling” of the previous system took place gradually, without abrupt leaps and changes, because Pinochet’s presence remained on the political arena even after the transfer of his powers.

Gradually, the democratic process began to deepen. Under Ricardo Lagos (Spanish – Ricardo Froilán Lagos Escobar) in May 2005, the Chilean Parliament approved major bills. Since then, all senators without exception must be elected by Chilean citizens by direct vote. The second decree allowed the head of state to appoint and replace commanders of the military branches.

The President began to run not for six years, as before, but for four years with the right to be nominated again after one term after the end of the previous mandate. According to such a scheme, the successor to Lagos, Michelle Bachelet (Spanish – Verónica Michelle Bachelet Jeria), who pursued a ramified social policy and promoted the idea of adopting a new main constituent document of the state, acted, but in the end she failed to achieve the consent of the opposition parties.

The problem of adopting the Constitution has long turned into a heavy burden of the Pinochet era. The current Chilean leader, a representative of the “right-wing” forces, Sebastian Piñera, hopes to enter the modern history of Chile as a figure who achieved the approval of a new fundamental set of laws. The Chilean government faced new challenges following the National Plebiscite. The society has thoroughly supported the adoption of the new Constitution. However, now the Chilean leadership needs to launch a large-scale mechanism for the preparation and subsequent approval of the country’s main constituent document, which is already planned in the form of a referendum for the first half of 2022.